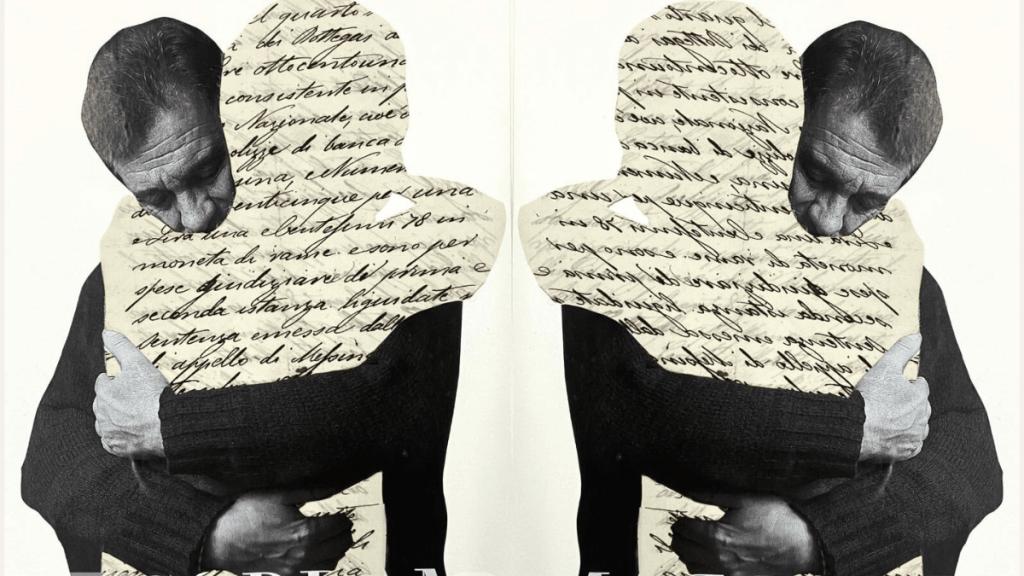

This is a passage I came across on Facebook and wanted to ensure it gets the airtime it deserves.

So many of us see ageing as something to be avoided to vain reasons but this article demonstrates the deeper and more painful part of ageing. It talks about the grief we carry from the many goodbyes we’ve had to endure. The parts of ourselves that no longer exist when we lose others.

…

We tend to imagine later life as a story about mirrors, waistlines, and relevance, a slow negotiation with surfaces. But Joyce Carol Oates words in the The Guardian turn that assumption inside out.

What she was really pointing to is a quieter, more devastating shift, the way time gradually thins the room until the people who once filled it are gone.

What makes her observation about aging so piercing is that it reframes the entire emotional project of growing older. Vanity, after all, is a problem with solutions, creams, jokes, denial, acceptance. It keeps the focus on the self. Loss pulls the focus outward. It forces an accounting of love. Each absence is proof of connection, and also of vulnerability. You don’t just lose people. You lose versions of yourself that only existed in their presence.

Psychologically, this helps explain why aging can feel heavier even when life looks stable on paper. The older we get, the more our inner world becomes populated by memories that no longer have living counterparts. There are fewer people who remember our childhood names, our first ambitions, the specific way we laughed in our twenties. The past doesn’t disappear, but it becomes less shared. That loneliness is different from being alone. It’s the loneliness of carrying a history that fewer and fewer people can help you carry.

Culturally, we don’t love to talk about this. Modern life prefers narratives of reinvention and resilience. We celebrate second acts, third chapters, and graceful adaptations. There’s value in that, of course. But it can flatten the truth. Grief isn’t something you overcome and leave behind. It accumulates. Joan Didion wrote about this with brutal clarity, insisting that grief has its own logic, its own stubborn refusal to be rushed. Virginia Woolf understood it too, how the dead continue to shape the living, how absence can be a kind of presence that never quite loosens its grip.

Oates has faced this reality in her own life. The sudden death of her husband, Raymond Smith, after decades of marriage marked her deeply and reshaped her later writing. Her memoir of widowhood is unsparing, almost shocking in its refusal to soften the blow. It echoes the same understanding she hinted at years earlier, that time doesn’t just move us forward. It also leaves us behind with fewer companions.

There’s also a moral implication here. If aging is about loss, then love becomes both the risk and the reward of being alive. To care deeply is to accept future grief as part of the deal. This can make youth seem deceptively light. It isn’t that young people love less, but that they haven’t yet had to live with the full cost of loving. Over time, that cost becomes visible. Birthdays turn into quiet inventories of who is no longer there to call.

In a society that often sidelines older people, this perspective asks for more tenderness. It suggests that what can look like bitterness or withdrawal may actually be exhaustion from carrying so many goodbyes. It also challenges the idea that wisdom comes neatly packaged. Sometimes what comes instead is a deeper sadness paired with a deeper compassion. When you’ve lost enough, you recognize loss in others more quickly.

The sentence also has literary implications. It explains why so many late works by writers feel different, more pared down, more haunted. There’s less interest in proving oneself and more urgency in telling the truth as it’s been lived.

Joyce Carol Oates has sometimes been criticized for her relentless darkness, her refusal to offer comfort. But this may be precisely her honesty. To look directly at aging without flinching is to admit that it is, in many ways, an education in mourning.

And yet, there’s something quietly affirming here too. If the pain of growing older comes from losing people we love, then a life without that pain would be a life without deep attachment. The ache is the evidence. It means we showed up. We were changed by others. We let ourselves be marked.

That doesn’t make aging easier. But it makes it meaningful. And it asks us to treat one another, at every age, with a little more patience. We’re all carrying someone who is no longer walking beside us.

Leave a comment